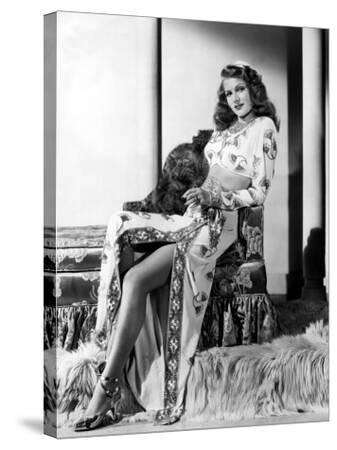

This is when she does that shit with her hair.” It’s not just lust on his face, but appreciation of her beauty and the joy that it brings. In the 1994 film adaptation of King’s book, the prisoners gather in the mess hall to watch Gilda, and right before she first appears, Morgan Freeman says to Tim Robbins, “This is the part I really like. In 1982, Stephen King wrote Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, a novella in which Hayworth’s pinup photo hides the hole dug in the wall. In 1948, in De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, Antonio is in the process of putting up a Gilda poster when his bike is stolen. In 1946, the United States conducted a couple of atomic bomb tests on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The shadow of Rita Hayworth in Gilda has stretched across the culture for almost seventy years now. In the booklet accompanying the Criterion release (a booklet which, importantly, folds out into a large photo of Gilda in her iconic black sheath dress, smoking a cigarette), film writer Sheila O’Malley writes of its cinematic legacy: This visage appeared in films as diverse as Stephen King’s The Shawshank Redemption and Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves.

The scene in which Hayworth’s luminescent visage is introduced made such a lasting impact on audiences – and not just contemporary ones but those that, even 50 years later, are fascinated with her performance – that it became a kind of meta-cinematic object. Such serious treatment of both the talent and dogged perseverance of the female talent that was so fundamental to Hollywood’s heyday is rare, and its inclusion in the Criterion Collection of Gilda is a testament to the sea change in both critical and popular memory of the contribution women like Hayworth made not only to American culture but to film culture as well.

#1946 rita hayworth film tv

What stands out in the short biographical documentary, which is narrated at turns by Joseph Cotton and Hayworth herself, is Rita’s lifelong commitment to hard work and her willingness to push herself beyond her comfort zone in order to achieve success.įor an actress billed (and remembered) so consistently as one of Hollywood’s most iconic sex symbols, the short TV special does a fantastic job of both humanizing her and dignifying her career as a performer and dramatic actress. The best inclusion is a 1964 Hollywood and the Stars TV special on “The Odyssey of Rita Hayworth”, which charts her career from her early childhood as part of a family of dancers to her meteoric rise to Hollywood fame. Each of these is enjoyable, if lackluster compared to the kinds of special features one is used to finding on Criterion editions. It comes with a 2010 commentary from film critic Richard Schickel, an interview with filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Baz Luhrmann on their love for the film, and a video essay by film noir historian Eddie Muller on Gilda‘s queer legacy. Perhaps because of the excellent quality of the transfer and the satisfaction of finally having Gilda on blu-Ray, it’s easy to forgive the DVD’s relative lack of usual Criterion extras. Indeed, it’s one of the finest pieces of entertainment that the American film industry has produced. It has spawned dozens of scholarly articles on a range of topics. It’s a real “aficionado” film, and yet, it has an undeniable popular appeal. It’s beautiful, classic, important, and thoroughly complex. Gilda is, perhaps, the one film that most thoroughly embodies the spirit of the Criterion enterprise. If ever a Criterion Collection film release was long overdue, Charles Vidor’s Gilda (1946) is that film.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)